---

title: Beta-density selection models for meta-analysis

date: '2024-11-08'

categories:

- effect size

- distribution theory

- selective reporting

execute:

echo: false

code-fold: true

bibliography: "../selection-references.bib"

csl: "../apa.csl"

link-citations: true

code-tools: true

toc: true

css: styles.css

crossref:

eq-prefix: ""

---

I still have meta-analytic selection models on the brain.

As part of [an IES-funded project](https://ies.ed.gov/funding/grantsearch/details.asp?ID=5730) with [colleagues from the American Institutes for Research](https://www.air.org/mosaic/experts), I've been working on developing methods for estimating selection models that can accommodate dependent effect sizes.

We're looking at two variations of p-value selection models: step-function selection models similar to those proposed by @hedges1992modeling and @vevea1995general and beta-density models as developed in @Citkowicz2017parsimonious.

Both models fall within the broader class of $p$-value selection models, which make explicit assumptions about the probability of observing an effect size, given its statistical significance level and sign.

I've already described how step-function models work (see [this previous post](/posts/step-function-selection-models/)) and, as a bit of a detour, I also took a stab at demystifying the [Copas selection model](/posts/Copas-selection-models).

In this post, I'll look at the beta-density model, highlight how it differs from step-function models, and do a deep dive into some of the tweaks to the model that we've implemented as part of the project.

# The beta-density selection model

The beta-density selection model is another entry in the class of $p$-value selection models.

Like the step-function model, it consists of a set of assumptions about

how effect size estimates are generated prior to selection (the _evidence-generation process_), and a set of assumptions about how selective reporting happens as a function of the effect size estimates (the _selective reporting process_).

In both the beta-density and step-function models, the evidence-generating process is a random effects model:

$$

T_i^* | \sigma_i^* \sim N\left(\mu, \tau^2 + \left(\sigma_i^*\right)^2\right),

$$ {#eq-evidence-generation}

where $T_i^*$ denotes an effect size estimate prior to selective reporting and $\sigma_i^*$ denotes its (known) standard error.[^metareg]

[^metareg]: With either model, the evidence-generating process can be extended to include a meta-regression with predictors of the average effect size. This amounts to replacing $\mu$ with $\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{1i} + \cdots + \beta_p x_{pi}$ for some set of predictors $x_{1i},...,x_{pi}$. For present purposes, I'm not going to worry about this additional complexity.

The only difference between the beta-density and step-function selection models is the functional form of the selective reporting process.

Letting $O_i^*$ be an indicator equal to 1 if $T_i^*$ is reported and $p_i^* = 1 - \Phi\left(T_i^* / \sigma_i^*\right)$ be the one-sided p-value corresponding to the effect size estimate,

the selective reporting process describes the shape of $\text{Pr}(O_i^* = 1 | p_i^*)$.

The step-function model uses a piece-wise constant function with level shifts at analyst-specified significance thresholds (see @fig-step-fun).

The beta-density model instead uses...wait for it...a beta density kernel function, which can take on a variety of smooth shapes over the unit interval (see @fig-beta-dens).

::: {.column-body-outset layout-ncol=2}

```{r}

#| label: fig-step-fun

#| fig-width: 5

#| fig-height: 3

#| fig-cap: "Two-step selection model with $\\lambda_1 = 0.6, \\lambda_2 = 0.4$"

library(metaselection)

library(ggplot2)

pvals <- seq(0,1,.005)

step_sel <- step_fun(cut_vals = c(.025, .500), weights = c(0.6, 0.4))

beta_sel <- beta_fun(delta_1 = 0.5, delta_2 = 0.8, trunc_1 = .005, trunc_2 = 1 - .005)

dat <- data.frame(

p = pvals,

step = step_sel(pvals),

beta = beta_sel(pvals)

)

ggplot(dat, aes(x = pvals)) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0,1.1), expand = expansion(0,0)) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(0,1,0.2), expand = expansion(0,0)) +

geom_vline(xintercept = c(0.025, .500), linetype = "dashed") +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_area(aes(y = step), fill = "darkgreen", alpha = 0.6) +

theme_minimal() +

labs(x = "p-value (one-sided)", y = "Selection probability")

```

```{r}

#| label: fig-beta-dens

#| fig-width: 5

#| fig-height: 3

#| fig-cap: "Beta-density selection model with $\\lambda_1 = 0.5, \\lambda_2 = 0.8$"

ggplot(dat, aes(x = pvals)) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0,1.1), expand = expansion(0,0)) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(0,1,0.2), expand = expansion(0,0)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_area(aes(y = beta), fill = "darkorange", alpha = 0.6) +

theme_minimal() +

labs(x = "p-value (one-sided)", y = "Selection probability")

```

:::

In the original formulation of the beta density model, the selection function is given by

$$

\text{Pr}(O_i^* = 1 | p_i^*) \propto \left(p_i^*\right)^{(\lambda_1 - 1)} \left(1 - p_i^*\right)^{(\lambda_2 - 1)},

$$

where the parameters $\lambda_1$ and $\lambda_2$ must be strictly greater than zero, and $\lambda_1 = \lambda_2 = 1$ corresponds to a constant probability of selection (i.e., no selective reporting bias). Because $p_i^*$ is a function of the effect size estimate and its standard error, the selection function can also be written as

$$

\text{Pr}(O_i^* = 1 | T_i^*, \sigma_i^*) \propto \left[\Phi(-T_i^* / \sigma_i^*)\right]^{(\lambda_1 - 1)} \left[\Phi(T_i^* / \sigma_i^*)\right]^{(\lambda_2 - 1)},

$$

where $\Phi()$ is the cumulative standard normal distribution.

In proposing the model, @Citkowicz2017parsimonious argued that the beta-density function provides a parsimonious expression of more complex forms of selective reporting than can easily be captured by a step function.

For instance, the beta density in @fig-beta-dens is smoothly declining from $p < .005$ through the psychologically salient thresholds $p = .025$ and $p = .05$ and beyond. In order to approximate such a smooth curve with a step function, one would have to use many thresholds and therefore many more than the two parameters of the beta density.

# A truncated beta-density

Although using smoothly varying selection probabilities may seem appealing, the beta density also comes with an important limitation, highlighted in a commentary by @hedges2017plausibility. For some parameter values, the beta density implies selection probabilities that differ by many orders of magnitude. These extreme differences in selection probability can imply implausible selection processes, in which hundreds of non-significant effect size estimates would need to go unreported to observe a sample of a few dozen findings. Extreme differences in selection probabilities make the model highly sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of some effect size estimates because the influence of each estimate is driven by the inverse of its selection probability [@hedges2017plausibility].

As a means to mitigate these issues with the beta density, we consider a modification of the model where the function is truncated at $p$-values larger or smaller than certain thresholds.

For user-specified thresholds $\alpha_1$ and $\alpha_2$, let $\tilde{p}_i^* = \min\{\max\{\alpha_1, p_i^*\}, \alpha_2\}$. The truncated beta density is then

$$

\text{Pr}(O_i^* = 1 | p_i^*) \propto (\tilde{p}_i^*)^{(\lambda_1 - 1)} \left(1 - \tilde{p}_i^*\right)^{(\lambda_2 - 1)},

$$ {#eq-selection-process}

Setting the truncation thresholds at psychologically salient levels such as $\alpha_1 = .025$ and $\alpha_2 = .975$ (which correspond to positive and negative effects that are statistically significant based on two-sided tests with $\alpha = .05$) gives something kind of like the step-function selection model, but with smoothly varying selection probabilities in the interior.

Alternately, one could set the second threshold at $\alpha_2 = .500$ (corresponding to an effect of zero) so that all negative effect size estimates have a constant probability of selection, but positive effect size estimates that are non-significant have smoothly varying selection probabilities up to the point where $p_i^* = .025$.

# Distribution of observed effect sizes

Just as with the step-function selection model, the assumptions of the evidence-generating process (@eq-evidence-generation) and the selection process (@eq-selection-process) can be combined to obtain the distribution of observed effect sizes,

with

$$

\begin{aligned}

\Pr(T_i = t | \sigma_i) &\propto \Pr\left(O_i^* = 1| T_i^* = t, \sigma_i^* = \sigma_i\right) \times \Pr(T_i^* = t| \sigma_i^* = \sigma_i) \\

&\propto \left[\Phi(-t / \sigma_i^*)\right]^{(\lambda_1 - 1)} \left[\Phi(t / \sigma_i^*)\right]^{(\lambda_2 - 1)} \times \frac{1}{\sqrt{\tau^2 + \sigma_i^2}} \phi\left(\frac{t - \mu}{\sqrt{\tau^2 + \sigma_i^2}}\right)

\end{aligned}

$$

Here is an interactive graph showing the distribution of the effects prior to selection (in grey) and the distribution of observed effect sizes (in blue) based on the truncated beta-density selection model. Initially, the truncation points are set at $\alpha_1 = .025$ and $\alpha_2 = .975$ and the selection parameters are set to $\lambda_1 = 0.5$ and $\lambda_2 = 0.8$, but you can change these however you like.

Below the effect size distribution are the moments of the distribution (computed numerically) and a graph of the truncated beta density that determines the selection probabilities.

```{ojs}

math = require("mathjs")

norm = import('https://unpkg.com/norm-dist@3.1.0/index.js?module')

function findprob(p, alp1, alp2, lam1, lam2) {

let p_ = math.min(math.max(p, alp1), alp2);

let prob = (p_)**(lam1 - 1) * (1 - p_)**(lam2 - 1);

return prob;

}

eta = math.sqrt(tau**2 + sigma**2)

max_p = {

if (lambda1 + lambda2 > 2) {

return (lambda1 - 1) / (lambda1 + lambda2 - 2);

} else if (lambda1 > lambda2) {

return alpha2;

} else {

return alpha1;

}

}

max_prob = findprob(max_p, alpha1, alpha2, lambda1, lambda2)

```

```{ojs}

pts = 201

dat = Array(pts).fill().map((element, index) => {

let t = mu - 3 * eta + index * eta * 6 / (pts - 1);

let p = 1 - norm.cdf(t / sigma);

let dt = norm.pdf((t - mu) / eta) / eta;

let prob = findprob(p, alpha1, alpha2, lambda1, lambda2);

return ({

t: t,

d_unselected: dt,

d_selected: prob * dt / max_prob

})

})

selfundat = Array(pts).fill().map((element, index) => {

let p = index / (pts - 1);

let prob = findprob(p, alpha1, alpha2, lambda1, lambda2);

return ({

p: p,

prob: prob

})

})

moments = {

let prob = 0;

let ET = 0;

let ET2 = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < pts; i++) {

prob += dat[i].d_selected;

ET += dat[i].t * dat[i].d_selected;

ET2 += dat[i].t**2 * dat[i].d_selected;

}

let ET_val = ET / prob;

let VT_val = ET2 / prob - ET_val**2;

return ({

Ai: prob * 6 * eta / (pts - 1),

ET: ET_val,

SDT: math.sqrt(VT_val)

})

}

eta_toprint = eta.toFixed(3)

Ai_toprint = moments.Ai.toFixed(3)

ET_toprint = moments.ET.toFixed(3)

SDT_toprint = moments.SDT.toFixed(3)

```

:::::: {.grid .column-page}

::::: {.g-col-8 .center}

```{ojs}

Plot.plot({

height: 300,

width: 700,

y: {

grid: false,

label: "Density"

},

x: {

label: "Effect size estimate (Ti)"

},

marks: [

Plot.ruleY([0]),

Plot.ruleX([0]),

Plot.areaY(dat, {x: "t", y: "d_unselected", fillOpacity: 0.3}),

Plot.areaY(dat, {x: "t", y: "d_selected", fill: "blue", fillOpacity: 0.5}),

Plot.lineY(dat, {x: "t", y: "d_selected", stroke: "blue"})

]

})

```

:::: {.grid}

:::{.g-col-4 .moments}

```{ojs}

tex`

\begin{aligned}

\Pr(O_i^* = 1) &= ${Ai_toprint} \\

\mu &= ${mu} \\

\mathbb{E}\left(T_i\right) &= ${ET_toprint} \\

\eta_i &= ${eta_toprint} \\

\sqrt{\mathbb{V}\left(T_i\right)} &= ${SDT_toprint}

\end{aligned}`

```

:::

::: {.g-col-8 .center}

```{ojs}

Plot.plot({

height: 200,

width: 400,

y: {

grid: false,

label: "Selection probability"

},

x: {

label: "p-value (one-sided)"

},

marks: [

Plot.ruleY([0]),

Plot.ruleX([0,1]),

Plot.areaY(selfundat, {x: "p", y: "prob", fill: "green", fillOpacity: 0.5}),

Plot.lineY(selfundat, {x: "p", y: "prob", stroke: "green"})

]

})

```

:::

::::

:::::

::::: {.g-col-4}

```{ojs}

//| panel: input

viewof mu = Inputs.range(

[-2, 2],

{value: 0.15, step: 0.01, label: tex`\mu`}

)

viewof tau = Inputs.range(

[0, 2],

{value: 0.10, step: 0.01, label: tex`\tau`}

)

viewof sigma = Inputs.range(

[0, 1],

{value: 0.20, step: 0.01, label: tex`\sigma_i`}

)

viewof alpha1 = Inputs.range(

[0, 1],

{value: 0.025, step: 0.005, label: tex`\alpha_1`}

)

viewof alpha2 = Inputs.range(

[0, 1],

{value: 0.975, step: 0.005, label: tex`\alpha_2`}

)

viewof lambda1 = Inputs.range(

[0, 5],

{value: 0.50, step: 0.01, label: tex`\lambda_1`}

)

viewof lambda2 = Inputs.range(

[0, 5],

{value: 0.80, step: 0.01, label: tex`\lambda_2`}

)

```

:::::

::::::

# Empirical example

@Citkowicz2017parsimonious presented an example of a meta-analysis where applying the original form of the beta-density selection model led to dramatically different findings from the summary meta-analysis. The data come from a synthesis by @baskerville2012systematic that examined the effects of practice facilitation on the uptake of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in primary care settings. The original meta-analysis found a large average effect indicating that facilitation improves adoption of EBPs, although there were also indications of publication bias based on an Egger's regression test. Fitting the beta-density model leads to much smaller effects.

However, @hedges2017plausibility criticized the beta-density results as involving an implausibly large degree of selection and noted that the estimated average effect is very sensitive to high-influence observations.

Does using a more strongly truncated beta density change this picture? I'll first work through the previously presented analyses, then examine the extent to which introducing truncation points for the beta density affects the model estimates.

## Summary random effects model

Here are the random effects meta-analysis results, estimated using maximum likelihood for consistency with subsequent modeling:

```{r}

#| echo: true

library(tibble)

library(dplyr)

library(tidyr)

library(metafor)

Baskerville <- tribble(

~ SMD, ~ V, ~ Blinded,

1.01, 0.2704, 'B',

0.82, 0.2116, 'O',

0.59, 0.0529, 'O',

0.44, 0.0324, 'O',

0.84, 0.0841, 'B',

0.73, 0.0841, 'O',

1.12, 0.1296, 'B',

0.04, 0.1369, 'B',

0.24, 0.0225, 'O',

0.32, 0.1600, 'O',

1.04, 0.1024, 'O',

1.31, 0.3249, 'B',

0.59, 0.0841, 'B',

0.66, 0.0361, 'O',

0.62, 0.0961, 'B',

0.47, 0.0729, 'B',

1.08, 0.1024, 'O',

0.98, 0.1024, 'B',

0.26, 0.0324, 'B',

0.39, 0.0324, 'B',

0.60, 0.0961, 'B',

0.94, 0.2809, 'B',

0.11, 0.0729, 'B'

)

RE_fit <- rma(yi = SMD, vi = V, data = Baskerville, method = "ML")

RE_fit

```

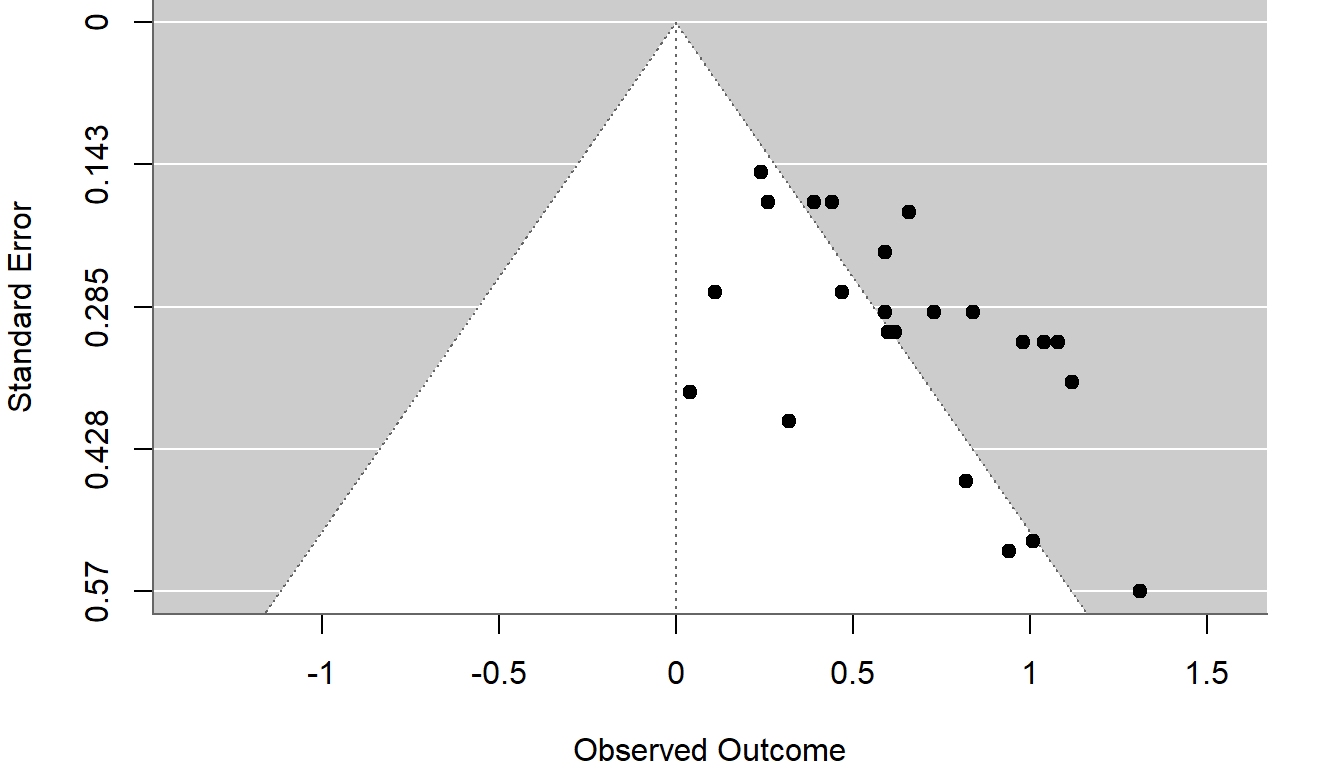

The average effect estimate is $\hat\mu = `r round(RE_fit$b, 3)`$, with a 95% CI of $[`r round(RE_fit$ci.lb, 3)`, `r round(RE_fit$ci.ub, 3)`]$. Here is a funnel plot of the effect size estimates against standard errors, with contours indicating regions of statistical significance for positive and negative estimates:

```{r}

#| label: fig-funnel

#| fig-cap: "Funnel plot of effect size estimates from the Baskerville meta-analysis"

#| echo: true

#| fig-width: 7

#| fig-height: 4

#| fig-retina: 2

#| out-width: 80%

par(mar=c(4,4,0,2))

funnel(RE_fit, refline = 0)

```

There's clearly asymmetry in the funnel plot, which can be an indication of selective reporting.

## Original beta-density model

@Citkowicz2017parsimonious fit the original form of the beta-density model to the data. This is now quite easy to do with the `metafor` package:

```{r}

#| echo: true

beta_fit <- selmodel(RE_fit, type = "beta")

beta_fit

```

The overall average effect size in the un-selected population is now estimated to be $\hat\mu = `r round(beta_fit$b[,1], 3)`$, 95% CI $[`r round(beta_fit$ci.lb, 3)`, `r round(beta_fit$ci.ub, 3)`]$, with selection parameters (called $\delta_1$ and $\delta_2$ in metafor) estimated as $\hat\lambda_1 = `r round(beta_fit$delta[1], 3)`$ and $\hat\lambda_2 = `r round(beta_fit$delta[2], 3)`$.

The same model can also be fit using our `metaselection` package:

```{r}

#| echo: true

library(metaselection)

Baskerville$se <- sqrt(Baskerville$V)

Baskerville$p <- with(Baskerville, pnorm(SMD / se, lower.tail = FALSE))

beta_sel <- selection_model(

data = Baskerville,

yi = SMD,

sei = se,

selection_type = "beta",

steps = c(1e-5, 1 - 1e-5),

vcov_type = "model-based"

)

summary(beta_sel)

```

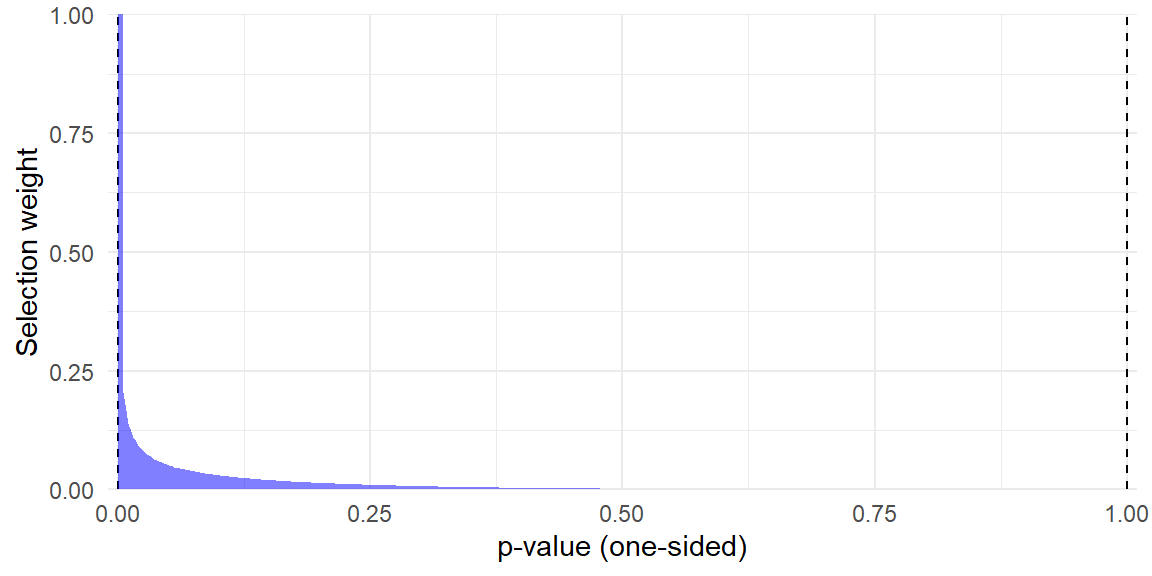

I will stick with the `metaselection` package for subsequent analysis because it allows the user to specify their own truncation points for the beta-density model. It also has some helper functions such as `selection_plot()` for graphing the estimated selection function:

```{r}

#| echo: true

#| fig-width: 6

#| fig-height: 3

#| out-width: 70%

selection_plot(beta_sel, ref_pval = Baskerville$p[14]) +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(0,1)) +

theme_minimal()

```

## Hedges' critiques

::: {.column-margin}

```{r}

#| label: tbl-selection-probs

#| tbl-cap: Probabilities of selection relative to $\text{Pr}(O_i = 1 \vert p_i = .0005)$

selwts <- selection_wts(beta_sel, pvals = c(.0005,.001, .005, .01, .025, .05, .10, .5))

selwts$wt <- selwts$wt / selwts$wt[1]

selwts %>%

filter(p > .0005) %>%

knitr::kable(

digits = 3,

col.names = c("$p_i$", "$\\text{Pr}(O_i = 1 \\vert p_i)$")

)

```

:::

@hedges2017plausibility noted that the beta-density model for these data generates very extreme selection probabilities. Following along with his numerical example, @tbl-selection-probs reports the probability of observing effects for several different $p$-values, relative to the probability of observing a highly significant effect with $p = .0005$.

Notably, based on the estimated selection function, an effect with one-sided $p_i = .0005$ is over eight times more likely to be reported than an effect with $p = .025$ and nearly 500 times more likely to be reported than an effect of zero with $p_i = .500$. Quoth @hedges2017plausibility: "This seems like an extraordinarily high degree of selection" (p. 43).

Hedges goes on to explain how the estimated selection parameters can be used to infer the total number of effect sizes that would need to be _generated_ in order to obtain a sample of $k = 23$ observed effect sizes. The calculation involves the quantity

$$

A_i = \text{Pr}(O_i^* = 1 | \sigma_i^*) = \text{E}\left[\left.\Pr\left(O_i^* = 1| p_i^*\right) \right| \sigma_i^*\right],

$$

which is the overall probability of observing an effect size estimate in a study with standard error $\sigma_i^*$.^[@hedges2017plausibility denotes this quantity as $g_i(T_i)$.]

The inverse of $A_i$ is the expected number of effect size estimates that would need to be generated (including both those that are subsequently reported and those that remain unreported) in order to obtain one observed estimate.

A challenge here is that the selective reporting process is only identified up to a proportionality constant, so the _absolute_ probability of reporting cannot be estimated without making some further assumption.

Hedges approaches this by assuming that any effect size estimate with $p$-value equal to the smallest observed $p$-value will be reported with certainty, so that the proportionality constant becomes $w_{min} = (p_{min})^{\lambda_1 - 1} (1 - p_{min})^{\lambda_2 - 1}$.

Under this assumption, estimates of $A_i$ can be computed given the parameter estimates $\hat\mu$, $\hat\tau$, $\hat\lambda_1$, $\hat\lambda_2$ and the reference $p$-value $p_{min}$.

Taking the sum across the sample of observed standard errors, we can find an estimate of the number of effect sizes that would need to be generated:

$$

k_{gen} = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{1}{\hat{A}_i}.

$$

```{r}

lambda <- exp(beta_sel$est$Est[3:4])

Baskerville_Table1 <-

Baskerville %>%

mutate(Study = 1:n()) %>%

select(Study, T = SMD, SE = se, p) %>%

mutate(

wt = (p^(lambda[1] - 1)) * (1 - p)^(lambda[2] - 1),

wt_norm = wt / wt[14],

Ni = wt[14] / beta_sel$predictions$Ai,

omega = (1 / wt) / sum(1 / wt)

)

k_gen <- sum(Baskerville_Table1$Ni)

```

My attempt to reproduce the calculations in Table 1 of @hedges2017plausibility are displayed in @tbl-Hedges-Table1 below

Columns $T_i$ and $\sigma_i$ are the effect size estimates and standard errors reported by @baskerville2012systematic; $p_i$ is the one-sided $p$-value calculated from the data. The column labeled $\hat{w}(p_i)$ is the relative selection probability calculated from the estimated selection parameters $\hat\lambda_1 = `{r} round(lambda[1], 3)`, \hat\lambda_2 = `{r} round(lambda[2], 3)`$; the next column reports the same quantities, standardized by the relative probability of observation 14, which has the smallest reported $p$-value of $p_{min} = `{r} round(Baskerville$p[14], 5)`$.

Using the beta-density parameter estimates and standardizing to the minimum observed $p$-value, I calculate the probability of observing effect size estimates with each observed standard error.

The inverse of this quantity is the number of generated effect sizes one would need to produce a single observed effect size estimate; it is reported in the column labeled $\hat{A}_i^{-1}$.

Totalling these, I find $k_{gen} = `{r} round(k_gen, 0)`$.[^Hedges-discrepancy]

This implies quite a large number of missing studies that were conducted but not reported; Hedges argues that it is so large as to be implausible.

[^Hedges-discrepancy]: My estimate of $k_{gen}$ and the component quantities differ from those reported in Table 1 of @hedges2017plausibility; I am currently unsure why there is a discrepancy.

```{r}

#| label: tbl-Hedges-Table1

#| tbl-cap: Effect size estimates and computed values for beta density selection model estimated on Baskerville meta-analysis data

Baskerville_Table1 %>%

knitr::kable(

digits = 3,

col.names = c("Study","$T_i$","$\\sigma_i$","$p_i$", "$\\hat{w}(p_i)$", "$\\hat{w}(p_i) / \\hat{w}(p_{min})$","$\\hat{A}_i^{-1}$","$\\omega_i$")

)

```

Another, related limitation of the beta density model is that it puts extreme emphasis on a few individual observations that have low probability of selection.

@hedges2017plausibility noted that the influence of individual observations can be approximated by the inverse selection probabilities, such that the fraction of the total weight allocated to observation $i$ is

$$

\omega_i = \frac{1 / \hat{w}(p_i)}{\sum_{j=1}^k 1 / \hat{w}(p_j)}.

$$

The last column of @tbl-Hedges-Table1 reports these relative weights.

As Hedges noted, the overall average effect is strongly influenced by just two observations: study 8, which has approximately `{r} round(Baskerville_Table1$omega[8] * 100)`% of the weight, and study 23, which has approximately `{r} round(Baskerville_Table1$omega[23] * 100)`% of the weight.

## Sensitivity to truncation points

Does introducing truncation points into the beta density selection function change this picture in any meaningful way? My intuition is that using truncation points connected to psychologically salient thresholds (such as $\alpha_1 = .025$ and $\alpha_2 = .50$ or $.975$) should tend to moderate things in terms of both the implied overall degree of selection and the degree to which individual observations influence the model results. Here's what happens if I use truncation points corresponding to the usual 2-sided significance threshold of $\alpha = .05$:

```{r}

beta_trunc <- selection_model(

data = Baskerville,

yi = SMD,

sei = se,

selection_type = "beta",

steps = c(.025, .975),

vcov_type = "model-based"

)

summary(beta_trunc)

```

Under the truncated beta density, the estimated average effect size increases to $\hat\mu = `r round(beta_trunc$est$Est[1], 3)`$, but with much greater uncertainty, 95% CI $[`r round(beta_trunc$est$CI_lo[1], 3)`, `r round(beta_trunc$est$CI_hi[1], 3)`]$.

Contributing to this additional uncertainty is the larger estimate of between-study heterogeneity, $\tau^2 = `r round(exp(beta_trunc$est$Est[2]), 3)`$.

The selection parameters are now estimated as $\hat\lambda_1 \approx `r round(exp(beta_trunc$est$Est[3]), 3)`$ and $\hat\lambda_2 = `r round(exp(beta_trunc$est$Est[4]), 3)`$.

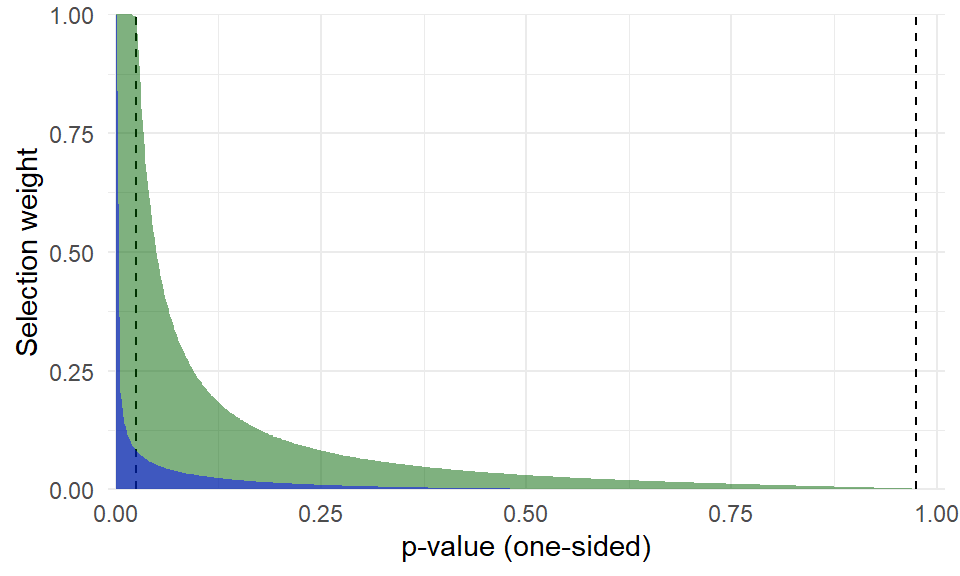

```{r}

#| label: fig-selection-functions

#| fig-cap: Estimated selection function under the truncated beta density model (green) and original beta density model (blue).

#| fig-width: 5

#| fig-height: 3

#| fig-retina: 2

#| out-width: 80%

untrunc_selection_curve <-

selection_wts(beta_sel, pvals = seq(0,1,.005), ref_pval = Baskerville$p[14]) %>%

mutate(wt = pmin(wt, 1))

selection_plot(beta_trunc, fill = "darkgreen") +

geom_area(data = untrunc_selection_curve, fill = "blue", alpha = 0.5) +

theme_minimal()

lambda <- exp(beta_trunc$est$Est[3:4])

Ni <- (.025^(lambda[1] - 1)) * (.975^(lambda[2] - 1)) / beta_trunc$predictions$Ai

k_gen <- sum(Ni)

Baskerville$Ni_trunc <- Ni

```

@fig-selection-functions is a graph of the estimated selection function. The green area is the selection function based on the truncated beta density model; for reference, the blue area is the selection function from the previous, untruncated model.

The model with truncation points does indicate a more moderate degree of selective reporting, although it still represents a fairly strong degree of selection.

The estimated selection parameters imply that $k_{gen} = `r round(k_gen)`$ effect sizes would need to have been generated to produce a sample of 23 observed effects---this is large but not nearly so far outside the realm of plausible as with the untruncated beta density.

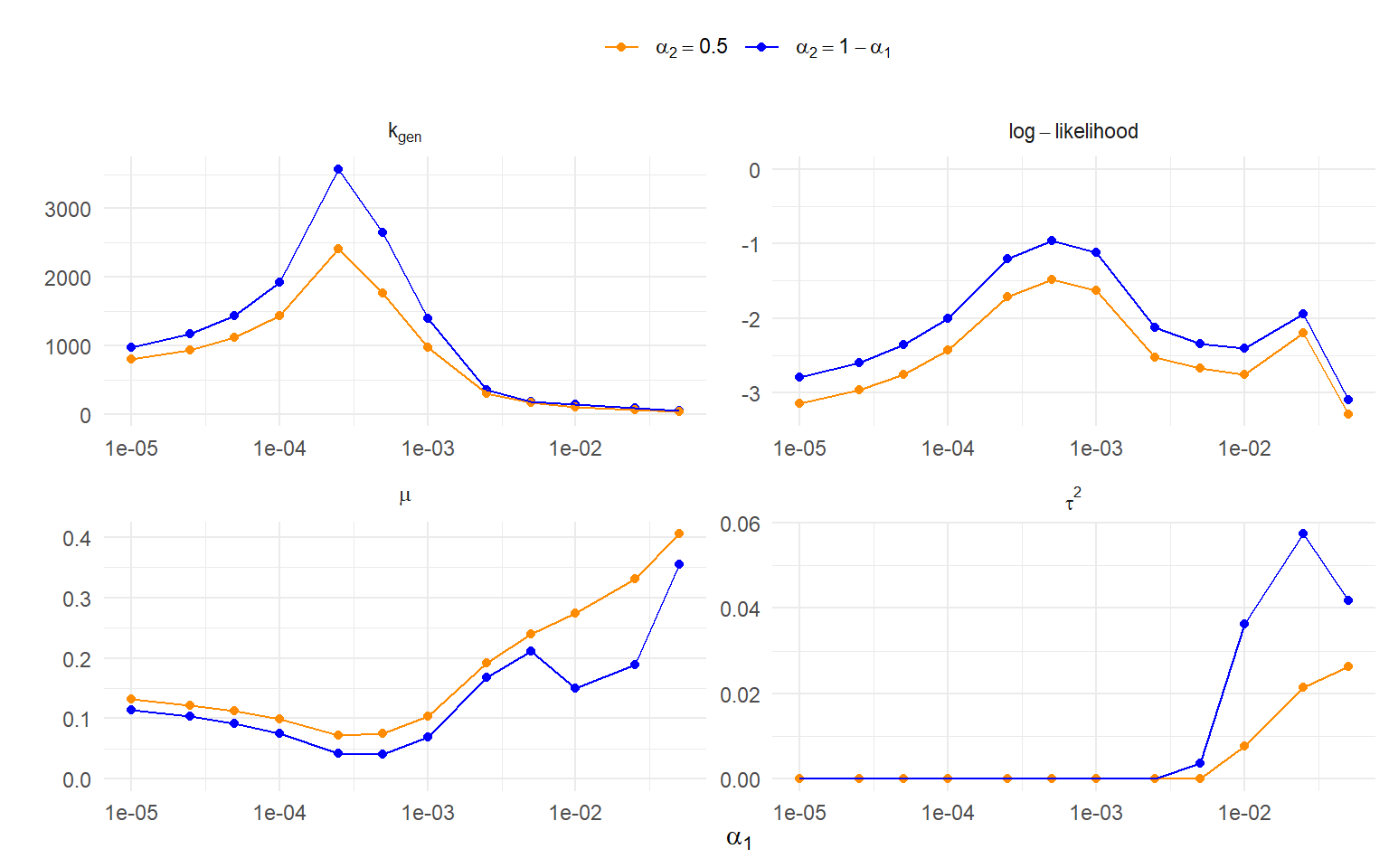

To get a more systematic sense of how sensitive the results are to the use of truncation points, I re-estimated the model many times with a range of different truncation points. For the left-hand truncation, I looked at $\alpha_1$ ranging from $10^{-5}$ to $10^{-2}$ and then also $\alpha_1 = .025$ and $\alpha_1 = .05$; for every one of these values, I looked at two different right-hand truncation points, first setting $\alpha_2 = 1 - \alpha_1$ and then fixing $\alpha_2 = .5$. With each model, I tracked the maximum log-likelihood, estimated mean and variance of the effects prior to selective reporting, and the total number of generated effects ($k_{gen}$) implied by the fitted model. The results are depicted in @fig-parameter-sensitivity.

```{r}

#| cache: true

#| results: hide

fit_fun <- function(alpha1, alpha2 = 1 - alpha1) {

beta_fit <- selection_model(

data = Baskerville,

yi = SMD,

sei = se,

selection_type = "beta",

steps = c(alpha1, alpha2),

vcov_type = "model-based"

)

lambda <- exp(beta_fit$est$Est[3:4])

Table1 <-

Baskerville %>%

mutate(

Study = 1:n(),

p_star = pmin(pmax(alpha1, p), alpha2),

wt = (p_star^(lambda[1] - 1)) * (1 - p_star)^(lambda[2] - 1),

wt_norm = wt / wt[14],

Ni = wt[14] / beta_fit$predictions$Ai,

omega = (1 / wt) / sum(1 / wt)

)

summary_measures <- tibble(

param = c("k_gen","log-likelihood", "omega"),

Est = c(sum(Table1$Ni), as.numeric(logLik(beta_fit)), NA),

wt = c(NA, NA, list(select(Table1, Study, Ni, omega)))

)

capture.output(param_ests <- print(beta_fit))

bind_rows(param_ests, summary_measures)

}

trunc_points <- expand_grid(

alpha1 = c(1e-5, 2.5e-5, 5e-5, 1e-4, 2.5e-4, 5e-4, 1e-3, 2.5e-3, 5e-3, 1e-2, 0.025, 0.05),

alpha2 = c(NA, 0.5)

) %>%

mutate(

alpha2 = if_else(is.na(alpha2), 1 - alpha1, alpha2)

)

library(future)

library(furrr)

plan(multisession)

beta_sens <-

trunc_points %>%

mutate(

res = future_pmap(., fit_fun)

) %>%

unnest(res)

```

```{r}

#| label: fig-parameter-sensitivity

#| fig-cap: Sensitivity analysis for the beta density model across varying truncation points

#| fig-align: center

#| fig-width: 8

#| fig-height: 5

#| fig-retina: 2

#| out-width: 100%

beta_sens_clean <-

beta_sens %>%

filter(param %in% c("beta","tau2","k_gen","log-likelihood")) %>%

select(-wt) %>%

mutate(

alpha2 = if_else(alpha2 == 0.5, "alpha[2] == 0.5", "alpha[2] == 1 - alpha[1]"),

param = factor(

param,

levels = c("k_gen", "log-likelihood", "beta", "tau2"),

labels = c("k[gen]","log-likelihood","mu","tau^2")

)

)

ggplot(beta_sens_clean) +

aes(alpha1, Est, color = alpha2) +

geom_point() + geom_line() +

expand_limits(y = 0) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_x_log10() +

scale_color_manual(values = c("alpha[2] == 0.5" = "darkorange", "alpha[2] == 1 - alpha[1]" = "blue"), labels = str2expression) +

facet_wrap(~ param, scales = "free", labeller = "label_parsed") +

labs(

x = expression(alpha[1]),

y = "",

color = ""

) +

theme(legend.position = "top")

```

In the top left-hand panel of @fig-parameter-sensitivity, it can be seen that the estimate of $k_{gen}$ is _strongly_ influenced by the truncation point.

Models with $\alpha_1 = 2 \times 10^{-4}$ and neighboring truncation points produce extremely high estimates, with $k_{gen} > 2500$.

Models with more psychologically relevant truncation points of $\alpha_1 = .01$ or $.025$ lead to much more moderated estimates with $k_{gen} < 150$.

The top right-hand panel shows the log-likelihood of models with different truncation points.

Models where $\alpha_2 = 1 - \alpha_1$ consistently have higher likelihood than those with the right-hand truncation point fixed to $\alpha_2 = .5$.

Of those examined, the truncation point with the highest overall likelihood is $\alpha_1 = 5 \times 10^{-4}$, which is rather curious.

The bottom panels of @fig-parameter-sensitivity depict the parameter estimates $\hat\mu$ and $\hat\tau^2$; $\hat\mu$ is fairly sensitive to the choice of truncation point, though $\hat\tau^2$ is sensitive only for larger truncation points of $\alpha_1 \geq .01$.

```{r}

#| label: fig-weight-sensitivity

#| fig-cap: Sensitivity of approximate weights $\omega_i$ under the beta density model across varying truncation points

#| fig-align: center

#| fig-width: 8

#| fig-height: 4

#| fig-retina: 2

#| out-width: 100%

beta_sens_omega <-

beta_sens %>%

filter(param == "omega") %>%

select(alpha1, alpha2, wt) %>%

unnest(wt) %>%

mutate(

alpha2 = if_else(alpha2 == 0.5, "alpha[2] == 0.5", "alpha[2] == 1 - alpha[1]"),

alpha2 = factor(alpha2, levels = c("alpha[2] == 1 - alpha[1]", "alpha[2] == 0.5"))

)

ggplot(beta_sens_omega) +

aes(alpha1, omega, color = factor(Study)) +

geom_point() + geom_line() +

expand_limits(y = 0) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_x_log10() +

facet_wrap(~ alpha2, scales = "fixed", labeller = "label_parsed") +

labs(

x = expression(alpha[1]),

y = expression(omega[i])

) +

theme(legend.position = "none")

study_8_wt <-

beta_sens_omega %>%

filter(alpha1 == .025, alpha2 == "alpha[2] == 1 - alpha[1]", Study == 8)

top3_wt <-

beta_sens_omega %>%

filter(alpha2 == "alpha[2] == 1 - alpha[1]", Study %in% c(8, 10, 23)) %>%

group_by(alpha1) %>%

summarize(omega = sum(omega)) %>%

filter(alpha1 == .025)

```

@fig-weight-sensitivity plots the fraction of the total weight (i.e., the $\omega_i$ values for each effect size) assigned to each effect size as a function of the left-hand truncation point; the left panel shows the weights when $\alpha_2 = 1 - \alpha_1$ and the right panel shows the same quantities from the slightly lower-likelihood models with $\alpha_2 = 0.5$.

Across both panels, the highest-influence observation (Study $i = 8$) becomes less so when $\alpha_1$ is set to higher truncation points.

When $\alpha_1 = .025$, it receives `{r} round(study_8_wt$omega * 100)`% of the total weight, compared to almost 50% in the untruncated model.

Still, it remains strongly influential.

The next-most influential observation (Study $i = 23$) has a fairly stable weight across all truncation points, and the third-most influential observation (Study $i = 10$) grows moreso for higher truncation points.

Even in the model with truncation points $\alpha_1 = .025, \alpha_2 = .975$, these three points still account for

`{r} round(top3_wt$omega * 100)`% of the total weight.

Looking across all of the model outputs, it seems that adding truncation points to the beta density is consequential, in that the model results are generally sensitive to the specific truncation points chosen.

In this example, using psychologically salient truncation points led to less extreme estimates of selection, with less implausible implications, but also yieleded estimates that are still strongly influenced by a few data points.

# Comments

The re-analysis that I have presented is, of course, just one example of how the truncated beta density selection model might be applied---other datasets will have different features and might show a different degree of sensitivity to the truncation points.

Still, this exercise has got me thinking about what more is needed to actually use meta-analytic selection models in practice.

For one, I like the $k_{gen}$ statistic and think it's pretty evocative.

For a proper analysis, it should come with measures of uncertainty, so working out a standard error and confidence interval to go along with the point estimate seems useful and necessary.

For another, it seems to me that there's a need for more thinking, tools, and guidance about how to choose a model specification (...how to _select_ a selection model, if you will...) and assess its fit and appropriateness.

The $k_{gen}$ statistic is one tool for building some intuition about a selection model.

@hedges1992modeling suggests another, which is to examine the distribution of $p$-values in the observed sample and consider whether and how it differs from the distribution of reported p-values implied by a fitted model.[^Bayes]

I think there might be still other diagnostics that could be worth exploring.

For instance, one could use the reporting probabilities from the estimated selection model to estimate not only the _total_ number of generated studies, but also the distribution of standard errors in the evidence base prior to selective reporting.

Here's a hacky attempt at representing this:

[^Bayes]: In a Bayesian framework, one might refine this further by simulating from the posterior predictive distribution of reported $p$-values.

```{r}

#| label: fig-SE-distribution

#| fig-cap: Distribution of standard errors across observed effect sizes and across all generated effect sizes (observed and unreported)

#| fig-align: center

#| fig-width: 5

#| fig-height: 3

#| fig-retina: 2

#| out-width: 60%

ggplot(Baskerville) +

geom_density(aes(x = se, y = after_stat(scaled * k_gen / 23), weight = Ni), alpha = .5, fill = "darkgrey", color = "darkgrey") +

geom_density(aes(x = se, y = after_stat(scaled)), alpha = .5, fill = "darkgreen", color = "darkgreen") +

labs(

x = "Standard error",

y = ""

) +

theme_minimal()

```

The green density shows the distribution of standard errors for the 23 reported effect sizes.

The larger grey density shows the distribution of standard errors for all _generated_ effect sizes, as implied by the truncated beta density model.

The plot suggests that many of the unobserved effect sizes would be from relatively larger studies (with standard errors of 0.3 or less), even though the probability of going unreported is larger for smaller studies.

Other interesting diagnostics might be to consider how $\text{E}(T_i | O_i^* = 1, \sigma_i)$ varies with $\sigma_i$ or how $A_i = \text{Pr}(O_i^* = 1 | \sigma_i)$ varies with $\sigma_i$.

Finally, pulling out a bit, working through this stuff has only reinforced my sense that there's still a real need for guidance about how to examine selective reporting bias in actual, empirical meta-analysis projects.

Right now, it feels to me like the methodological literature is kind of a mess.

_Lots_ of tools have been proposed, but uptake seems slow and pretty haphazard (based on my own informal experience) and the main advice I hear is to throw spaghetti at the wall and run _lots_ of different analyses.

This leaves it on the meta-analyst to figure out what to conclude when all those analyses don't all tell a consistent story, which hardly seems fair or even feasible.

To get out of this fix, I think it will be fruitful to put more stock in and invest further in developing formal, generative models---whether that involves the beta density model, the [step function selection model](/posts/step-function-selection-models/), [the Copas model](/posts/Copas-selection-models), or some other form of selection model---and doing careful model assessment and critique.

Comments

The re-analysis that I have presented is, of course, just one example of how the truncated beta density selection model might be applied—other datasets will have different features and might show a different degree of sensitivity to the truncation points. Still, this exercise has got me thinking about what more is needed to actually use meta-analytic selection models in practice. For one, I like the

For another, it seems to me that there’s a need for more thinking, tools, and guidance about how to choose a model specification (…how to select a selection model, if you will…) and assess its fit and appropriateness. The

The green density shows the distribution of standard errors for the 23 reported effect sizes. The larger grey density shows the distribution of standard errors for all generated effect sizes, as implied by the truncated beta density model. The plot suggests that many of the unobserved effect sizes would be from relatively larger studies (with standard errors of 0.3 or less), even though the probability of going unreported is larger for smaller studies. Other interesting diagnostics might be to consider how

Finally, pulling out a bit, working through this stuff has only reinforced my sense that there’s still a real need for guidance about how to examine selective reporting bias in actual, empirical meta-analysis projects. Right now, it feels to me like the methodological literature is kind of a mess. Lots of tools have been proposed, but uptake seems slow and pretty haphazard (based on my own informal experience) and the main advice I hear is to throw spaghetti at the wall and run lots of different analyses. This leaves it on the meta-analyst to figure out what to conclude when all those analyses don’t all tell a consistent story, which hardly seems fair or even feasible. To get out of this fix, I think it will be fruitful to put more stock in and invest further in developing formal, generative models—whether that involves the beta density model, the step function selection model, the Copas model, or some other form of selection model—and doing careful model assessment and critique.